It’s 90 years since Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song was published – plus it’s the 30th anniversary of a centre dedicated to the Mearns novelist. Gayle pays a visit.

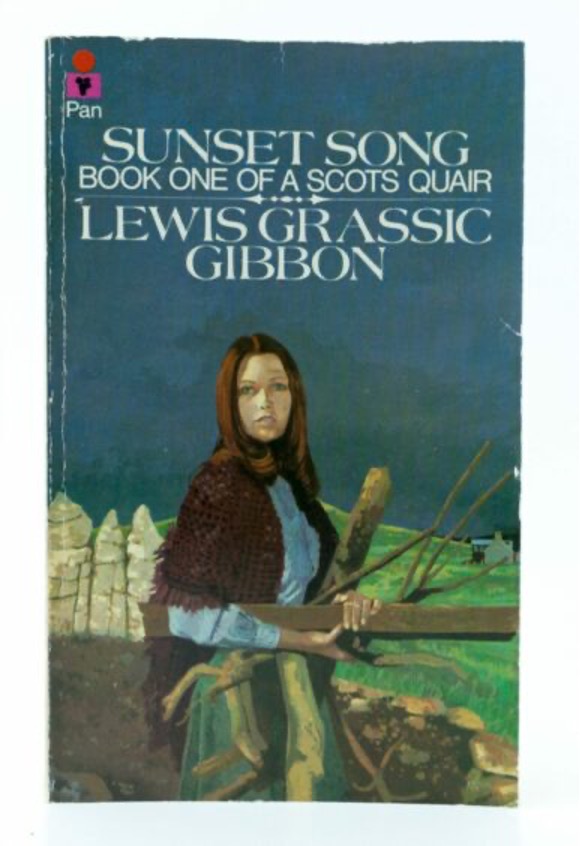

It’s an enduring classic, considered one of the most important Scottish novels of the 20th Century. Published in 1932 – 90 years ago – Sunset Song is the first part of Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s trilogy, A Scots Quair.

Set in the Mearns in the fictional parish of Kinraddie – modelled closely on Arbuthnott, where the author grew up – it tells a beautiful, though often heartbreaking, story.

Crushing poverty, the hard toil of earning a living from the land, the sternness of religion, the oppressive reality of life for women, and the coming of modernisation to traditional farming are among the main themes.

When Sunset Song was first published, some readers were shocked by its treatment of sex and childbirth, and its sometimes negative portrayals of family life. Some even believed it had been written by a woman. But it was Grassic Gibbon who penned Sunset Song, three years before he died aged 33.

Born James Leslie Mitchell in 1901 in Auchterless, and raised from the age of seven in Arbuthnott, he used the pseudonym Lewis Grassic Gibbon for the first time when his masterpiece was published in 1932.

The Grassic Gibbon Centre in Arbuthnott is a great place to start if you’re keen to find out more about the author’s life and works – and enjoy cake and coffee while you’re at it.

It’s a bit off the beaten track in the heart of the rolling Mearns countryside near the farm where Grassic Gibbon grew up and the churchyard where his ashes were laid to rest.

An exhibition tells his story through photographs, agricultural artefacts, clothing, display cases and story boards.

I met up with the centre’s chairman Jim Brown for a tour and to gain a deeper insight into the novelist.

It’s 30 years since the centre opened in 1992, so it’s an exciting time, with plans for a festival themed around “Women in the Mearns” in August.

“Mitchell’s upbringing in this area had a profound influence on his writings in later life,” Jim told me.

“He really understood parish life, the hierarchy, the land, and he observed the hardship and drudgery of farming and working on a croft.

“There’s a phrase about a parish being like an egg. The shell cracked when Gibbon wrote the story and all the gossip, misdeeds, weaknesses and frailties came gushing out. It wasn’t just about this parish, though; it could’ve been written in any parish in Scotland, but Arbuthnott took it to heart.”

Browsing the exhibition is eye-opening and I found myself drawn to Grassic Gibbon’s brown overcoat, hanging in a display case. To think – he wore this actual garment in the 1920s and 30s and it’s still in great nick!

More surprises include dozens of his personal items including a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles, a pencil, compass and an Ingersoll watch.

Rare and valuable books, many of which belonged to Grassic Gibbon, farm implements, crockery and household utensils are also on display.

And there’s a reconstruction of a burial kist – a nod to the author’s interest in archaeology.

Once we’d had a good look around, we drove to St Ternan’s Church where his ashes lie, marked with a headstone. It’s a peaceful, serene spot, despite the fact the wind was howling and the rain battering down.

I couldn’t leave the area without sampling the food at the centre’s cafe and I warmed up with a delicious bowl of potato and leek soup, coffee and slab of millionaire shortbread.

While Grassic Gibbon is best known for Sunset Song, Jim is a fan of his short stories, which he believes are under-rated. His favourites are in a collection called Smeddum, which means “true grit” and “determination”.

Jim said the author’s education was “his walk to school”, from the croft of Bloomfield to Arbuthnott School.

“It’s thought he walked about 14,000 miles back and forth to school. It’s reckoned he was influenced by the farmer and the roadman he passed. He saw the farmer as more visionary, more cheery and global than his father.”

His headmaster, Alexander Gray, spotted the genius in him when, aged 12, he wrote a remarkable essay. Later attending Stonehaven’s Mackie Academy, he fell foul of staff, and wrote of their “gaping ignorance”.

By 16 he was a reporter with the Aberdeen Journal and in 1919 went to work for the Scottish Farmer in Glasgow. As a young revolutionary, he falsified his newspaper expenses to help finance the political cause. He was sacked and had a nervous breakdown.

He joined the Army, then the RAF, as a clerk, returning to Bloomfield in 1923, and marrying childhood sweetheart Rebecca Middleton.

Then came The Thirteenth Disciple and between its publication in 1931 and 1934, he produced 15 of his 17 books.

But it was Aberdeen journalist Cuthbert Graham who goaded him into writing the trilogy that made his name.

Graham had criticised a Mitchell novel, asking: “How will Mr Mitchell develop? It is to be hoped he will settle down to give us novels of the North-east.”

Mitchell responded: “One of these days I’ll write that North-east novel he talks about.” And he did exactly that within six weeks – and Sunset Song was published in August 1932.

By February 1935, he developed a perforated ulcer. Peritonitis set in and he was dead before his 34th birthday.

Yet his literary legacy of 17 volumes produced in his short life testify to his skill as historian, essayist, biographer and fiction writer.

- For more details see grassicgibbon.com or go to the Facebook page.

- A leaflet of walks to places connected with Grassic Gibbon is available from the centre.